10 chemical facts that would impress your friends

In any odd situation talk about the science

If you try to get your friends together at a party and bombard them with amazing scientific facts, there’s a risk you’ll remember this party as the last one you were ever invited to. But if you happen to mention that the hydrogen in our bodies is 13.5 billion years old, you might just make a very strong impression. We’ve put together 10 facts which will help you amaze your friends (and yourself).

A car tire is one large molecule

The rubber that tires are made of is a polymer. This is the name for substances consisting of chains that are connected in large macro-molecules. The sulfur and silicic acid in the tire link the molecules of the polymer by little “bridges”. One large polymer molecule is formed, and the raw rubber mixture turns into elastic and durable rubber.

Money really doesn’t smell

At any rate, metallic money doesn’t. The characteristic smell of coins is not the smell of metal. It is produced by volatile compounds which form from organic substances (for example, human sweat) on contact with the coin. The metal itself simply serves as the catalyst of this reaction.

Of all the metals, only gold, cesium and copper do not have a silvery shine

Metals shine because they reflect light rays from their surface, and do not let them through, like glass, and do not absorb them like soot. A ray of sun can be imagined as a stream of elementary particles – photons. Most elementary metals reflect all the photons that hit them evenly, and the reflected light does not have colors.

In gold, cesium and copper atoms, the electrons absorb the energy of photons with long waves which correspond to the colors blue and purple, and these metals reflect the remaining red and yellow part of the spectrum. Gold has also been included in the Guinness Book of Records as the most plastic metal. So if you roll a piece of gold into foil with a thickness of 0.002 mm, sunlight will be visible through it. Although it will be a greenish color.

Water expands when it freezes

Usually when something cools, it becomes smaller. This also happens with water, but to a certain moment. The water molecule consists of one atom of oxygen and two atoms of hydrogen. As these atoms are bonded with each other, the molecules in the crystalline state need more space than in liquid state.

Every hydrogen atom in your body is around 13.5 billion years old

Hydrogen was the first chemical element that appeared at the beginning of the universe’s existence. All the hydrogen in the world has existed since that time, and new hydrogen has not appeared. This means that the age of every atom of hydrogen in the world, including those in the human body, is around 13.5 billion years old. A little later, as a result of nuclear synthesis some hydrogen atoms became atoms of helium, carbon and so on. But around 75% of the mass of the visible universe still consists of hydrogen. Helium accounts for another 25%, and all the other remaining elements for just 2%. But on Earth, the mass of hydrogen and helium put together does not exceed 1% of the total elements.

Where does an alcohol solution go?

Water solution of ethyl alcohol

If you mix a liter of water in a liter of ethyl alcohol, you get around 1.9 liters of solution. But don’t worry! No one’s spilled anything. The volume decreases because of the interpenetration of liquids. The alcohol molecules are larger than the water molecules, and the intermolecular space in the alcohol is also comparatively large. On mixing, some water molecules cozily arrange themselves among the alcohol molecules, and so the two liquids require a little less space. But their total weight remains the same as it did before mixing.

Technically, only several vitamins from group B have the right to be called vitamins

The word “vitamin” comes from vita (life) and amine (a nitrogenous organic compound). This word was first given to a preparation which was used in the early 20th century to treat chickens suffering from beriberi. For some time it was believed that every vitamin had to have a nitrogen atom. After the discovery of Vitamin C, which does not contain nitrogen, it became clear that this was not the case. Later it was found that nitrogen atoms are only contained in vitamins from group B. but the name had already caught on. But even not all of these turned out to be amines. Nevertheless, the name had already caught on. Over time, order was established in the classification of vitamins For example, the letter G vanished, which some scientists had previously given to vitamin B2, similar in its chemical composition to other vitamins from group B. And vitamin F was the name erroneously given to a group of several essential fatty acids. Now they have been demoted to “vitamin-like”, and the letter F has vanished from the list of vitamins.

Water can become solid at +20°C

Water turns solid at 20 degrees, if it contains methane. They must be mixed together at high pressure. Then water and methane sometimes form gaseous hydrate, which at a temperature of up to 20 degrees resembles packed snow.

Safety cushions are filled with poisonous sodium azide

Experiment with safety cushion

Many safety cushions contain toxic sodium azide (NaN3) – a salt of hydrozoic acid. In an accident with a strong collision, signals from data counters light a mixture on the basis of the poisonous salt. A reaction takes place with a large emission of harmless gaseous nitrogen, which inflates the cushion. The sodium that is formed as a subsidiary substance is also dangerous, but in safety cushions it is neutralized by potassium nitrate or silicon compounds.

Sometimes a postal address can be replaced with the names of elements

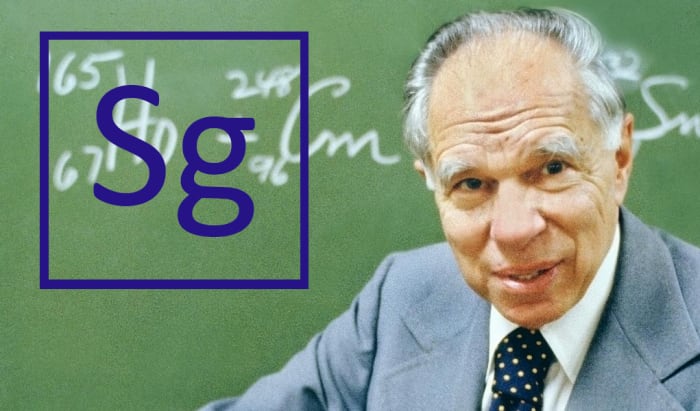

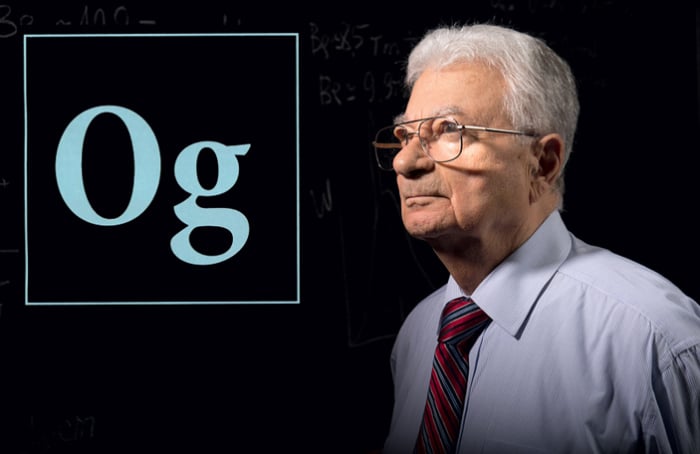

History knows just two cases when newly discovered elements were named in honor of a living scientist. They are the 106th element of Seaborgium, named after the American chemist Glenn Seaborg, and the 118th element of Oganesson, named after the Russian nuclear physicist Yury Oganessian. Additionally, only these two people could write their postal addresses with the names of chemical elements.

Seaborg (Sg, Seaborgium), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, (Lr, Lawrencium), Berkeley (Bk, Berkelium), state of California (Cf, Californium), United States of America (Am, Americium)

Oganessian (Og, Oganesson), Flerov laboratory (Fl, Flerovium), Dubna (Db, Dubnium), Russian Federation (Ru, Ruthenium; Ruthenia is the Latin name for Russia)