How it all explodes!

Alfred Nobel made a fortune from manufacturing dynamite from nitroglycerine, and used his wealth to found a prize named after himself.

If Nobel had also believed in the healing properties of nitroglycerine, this could have made his life easier. But assuming that this substance only gave people headaches, the inventor of dynamite suffered from heart disease for a long time. In the human body, nitroglycerine causes the nitric oxide molecule, NO, to break down, making the blood vessels expand. This property is used in the treatment of several cardiac diseases, as it ensures a full flow of blood to the heart. This was also the reason for the severe headaches among workers employed in the manufacture of explosives, including at Nobel’s factories. The structure of explosives is very diverse, but in most cases these molecules contain nitro groups – small groups of atoms consisting of one atom of nitrogen and two atoms of oxygen – NO₂ Of course, the ancient Chinese could not have known these details when they invented gunpowder. Some of them were simply lucky to live in areas with soil rich in salts of alkaline metals, where saltpeter (an important component of gunpowder) is found in its original form right on the surface of the ground. And gunpowder is a mixture of pulverized pieces of carbon, sulfur and saltpeter. When the mixture is heated, the saltpeter breaks down. Potassium nitrate KNO₂ forms, along with oxygen O₂, which ignites the remaining components. Boom!

“The Walking Dead” TV series on АМС

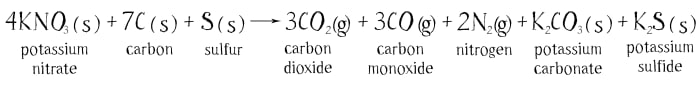

The chemical reaction of the explosion can be written down like this:

The letter “h” in brackets means that the substance is a solid, and the letter “g” means it is a gas. All of the reacting substances are solid, but as a result of the reaction eight gaseous molecules form: three molecules of hydrogen dioxide, three of carbon monoxide and two of nitrogen. It is the hot expanding gases forming in the swift combustion of the power that push the cannon ball or bullet. The forming solids of potassium carbonate and sulfide scatter in the form of tiny particles. They create the dense smoke that accompanies the explosion of the gunpowder.

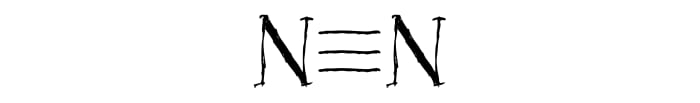

A large amount of heat is released in any explosion. This is because molecules in the two parts of the reaction equation have different strength of bonds between atoms. In the explosion of the nitric compounds, the extremely stable nitrogen molecule N2 is formed. The stability of this molecule comes from the triple bond that links the two nitrogen atoms.

The stability of the triple bond means that a lot of energy is required for an explosion. Accordingly, in the formation of the triple bond, a large amount of energy is freed up, which is also what happens in the explosion.

An explosion is a swift reaction. It is the speed that causes all the fatal consequences. If the reaction took place slowly, the heat released would disperse, and the gases would smoothly enter the environment, without causing significant pressure and not creating a shock wave. Atmospheric oxygen cannot enter the reaction swiftly enough. So oxygen must be contained in the explosive itself. This is why nitric compounds, in which nitrogen and oxygen are bonded together, are often explosive.

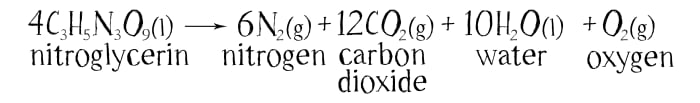

Unlike gunpowder, where on explosion a pressure of 6,000 atmospheres arises in one thousandth of a second, in an explosion of an equivalent amount of nitroglycerine, a pressure of 270,000 atmospheres is created in one millionth of a second.

While gunpowder is comparatively safe for use, nitroglycerine behaves terribly unpredictably. Nitroglycerine is a very unstable molecule. It explodes on heating or shaking.

Nevertheless, in the 19th century the need for nitroglycerine increased (especially in building shafts and tunnels), as its advantages over less powerful gunpowder became obvious.

Alfred Bernhard Nobel, who by 1868 owned factories in 11 countries in Europe and a company in San Francisco, began to look for ways to stabilize nitroglycerine without a loss of power. It was logical to try to turn the unpredictable liquid into a solid state. Nobel began to experiment, mixing oily nitroglycerine with neutral solid substances – wood chips, cement and charcoal dust. In the end, he decided on kieselguhr – crumbly silica with remains of diatomic algae. It was sometimes used for transporting nitroglycerine as a packaging material instead of woodchips. Kieselguhr could absorb leaking liquid nitroglycerine, while remaining porous. Tests showed that if liquid nitroglycerine was mixed with kieselguhr (3:1), a thick paste with the density of putty was formed. Kieselguhr separated the particles of nitroglycerine from one another, and this reduced the speed at which they broke down. This mixture could be given any form, it did not break down and did not explode on its own. Now the explosion could be controlled. Nobel called the mixture of nitroglycerine and kieselguhr dynamite (from the Greek dynamis – power).

Explosive nitro compounds are not used for military purposes. A mixture of saltpeter, sulfur and charcoal was used in mining from the early 17th century. Dynamite helped to build a road through the Rocky Mountains of Canada, build the Panama Canal with a length of 80 km, and destroy the underground mountain of Ripple Rock on the western seaboard of North America, which was a navigational hazard. Explosions lay the road for progress and free up space for new things. In the end, an explosion may just be terribly beautiful.

Controlled explosion of a watermelon

Sources:

‘Napoleon’s buttons’ Penne Le Couteur & Jay Burreson